Two years ago, one of the ten most awarded creative ideas in the world was “The Next Rembrandt.” It won two Grands Prix at Cannes among a haul of 16 Gold Lions.

Dutch financial services company ING had been sponsoring the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam since 2005. They wanted to let people know how marvellous they were, spending so much money on the arts.

The paradox within their brief to JWT Amsterdam was that while they valued the art of yesteryear, they also saw themselves as innovators. Apparently, they were the first bank in Holland to introduce fingerprint account log-in; and the first to enable the transfer of money through an app they called twyp.

Old and new. Then and now. Traditionalists and pioneers.

Normally the sort of bi-focal brief to make creative people froth at the mouth. But not in this instance. Creative director Bas Korsten had an idea. ]

Hey guys, let’s use data-driven AI to create a completely new painting from an artist whohas been dead for 347 years. Not a fake, not a replica but an original Rembrandt.

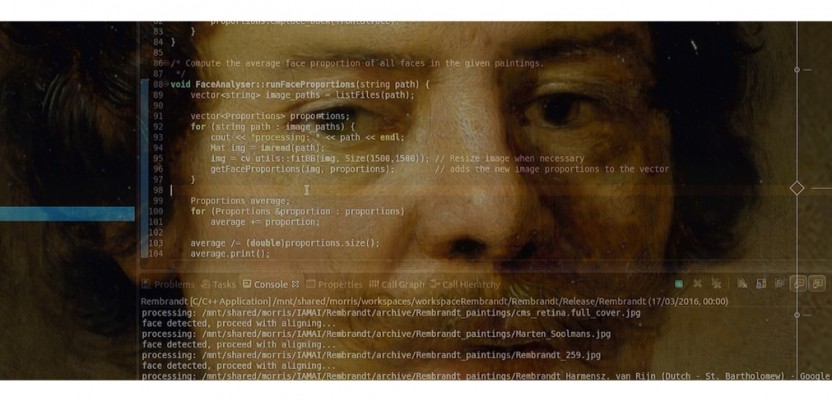

Thanks to a crew of data analysts, developers, engineers and art historians variously from Microsoft, Delft University of Technology and the Rembrandt Museum, a picture was duly made.

Every one of Rembrandt’s 346 known paintings was scanned. Facial recognition software worked out that the archetypal Rembrandt was of a middle-aged white man in black clothing with a white collar and a hat.

Pixel by pixel, data gave up the secrets of Rembrandt’s brushwork so that a 3D printer could mimic it in thirteen layers of applied paint.

When it was done, the picture was unveiled at the Rijksmuseum. Though everyone involved was at pains to say that it was nota work of art, it was given an entire gallery to itself. Dramatic lighting. Big screens with flickering algorithms either side, etc.

As if it was a work of art. Which, of course, it wasn’t. It was a map, not a portrait. It was, it is, the perfectly average Rembrandt.

And maybe that’s why some people, me among them, find it repellent.

Jonathan Jones, The Guardian’s art critic, wrote: “What a horrible, tasteless, insensitive and soulless travesty of all that is creative in human nature. What a vile product of our strange time when the best brains dedicate themselves to the stupidest challenges.”

One of the reasons for this violent critique of the picture is because it is further evidence of ‘the uncanny valley’.

The phrase was first coined by Jasia Reichardt in “Robots: Fact, Fiction and Prediction” to describe how weirdly horrible it is when humanoid objects look almost like us, but not quite.

What with AI, there are a lot of uncanny valleys about these days.

Have a listen to Sony’s attempt to recreate The Beatles. Every song the Fab Four recorded was fed to a bot, which then came up with a mash-up of Beatleness called “Daddy’s Car”. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSHZ_b05W7o

It is ghastly.

One theory about the uncanny valley is that when we look at a robot (or hear it speak, let alone sing) its very lifelessness reminds us of death.

So, that’s it then. “The Next Rembrandt” turns out to be the depiction of someone who never existed and is, if anything, the portrait of your own death. Which, philosophiocally speaking, is quite a mind f*ck.

Perhaps, because it has no meaning at all other than as an advertisement for a bank, it just reminds us of the astonishing genius of the original Rembrandt van Rijn.

Image from @strangerdimensions

Safnah IT Services September 1st, 2023, in the morning

Wow, this article explores the fascinating intersection of art, technology, and advertising. The idea of using data-driven AI to create an original Rembrandt painting is both innovative and controversial. While some may find it repellent and soulless, others see it as a thought-provoking representation of the uncanny valley and our complex relationship with technology. Ultimately, this project serves as a reminder of the incomparable genius of the original Rembrandt.