It may seem unlikely, but people on the autistic spectrum have been an integral part of the creative industry for decades, without the industry necessary knowing that. Thinking differently is not only a mantra but also a characteristic that is valued and sought after. The ability to imagine something unique has built careers, won accolades and created business success. Individuals with ASD are programmed to think different and have been an integral part of critical change for a very long time throughout history and today.

What is autism?

Autism is a complicated multidisciplinary neuro-developmental disorder. Those on the spectrum find it difficult to connect with others, often finding themselves in a disconnected space away from the people and environment around them. Where this starts to have an effect on an individual’s development in fact starts at an early age. Children learn a lot about behaviour and development by watching and imitating their parents and/or others around them. If someone isn’t seeing or connecting with these behaviours, they in turn don’t pick up on core developmental traits and at some point growth is stunted.

In order to identify autism in children, practitioners look at three bahvioural hallmarks: Lack of interaction and communication, restricted narrow interests and speech development delay. If a child displays one of those symptoms then it doesn’t necessarily mean that they are on the autistic spectrum. However, if he/she displays all three then there is reason to investigate further.

Today we generally refer to the autistic spectrum disorder rather than simply autism. This isn’t a binary condition, with identical symptoms and behaviour. Individuals on the spectrum are often very different from one another. The term itself is a bit of a catchall, applying to things such as autism, ADHD, Asperger’s Syndrome, PDD-NOS and variations of above conditions. As such, many people find it difficult to fully understand or appreciate what is meant by autism or the autistic spectrum disorder.

A recent history lesson.

It’s only recently that those on the spectrum have come to be properly diagnosed. As early as several decades back, coupled with societal stigma, proper diagnosis was overlooked. In some countries today, it is still seen as a child’s ailment, one that they will eventually grow out of. Until very recently, places like Russia didn’t recognize autism in adults and often classified it as schizophrenia treating patients with psychotropic drugs or looking for ways to remove people from society altogether. In some parts of the world, parents are encouraged to abandon children in orphanages and start again, assuring them that their life (both child and parent) will be better off that way.

Recent media tells us that autistic spectrum is diagnosed in 1 out of every 68 children, stimulating talks of a growing epidemic. It’s inconclusive whether there truly is an epidemic or whether it’s a case of misdiagnosis in previous years. Historians have taken this cue to revisit the way we view some of our historical figures and in some cases have postulated on possible or even likely diagnoses of ASD based on reported and recoded behaviour, which is an altogether legitimate conclusion given that ASD is diagnosed based on behavioural analysis.

Greg and Oscar.

I have two boys. Greg and Oscar. Both Greg and Oscar have been diagnosed with autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). Greg is a bit more severe than Oscar and both have very different symptoms. Oscar, who is three years old, has a speech delay but his key symptom is a challenge with transitions. He’s also very vocal about it. When things change or there’s a divergence from the familiar Oscar doesn’t react very well to that. Greg, who is five, is different in that he rarely makes a fuss. Greg has delayed speech and stimming/self-regulation such as flapping hands and the propensity to repeatedly trigger sounds and actions with toys or tools. In our home, it’s not unfamiliar to hear the first 3 seconds of the same song for hours. Both initially had poor eye contact, which has improved greatly in the past year and while there’s been tremendous development, direct communication is strained or even impossible at times.

I was a Canadian expat living in Moscow for sixteen years. We moved back to Canada from Russia about two years ago when Greg was diagnosed with ASD in order to give him the best chance at development. Russia isn’t a very good place to treat people on the spectrum so we wrapped things up, got on a plane, and arrived in Toronto ready to get started. Shortly afterwards, Oscar was diagnosed. Diagnosis generally happens around 4 to 5 years of age.

As we work with local practitioners, clinics and specialists and as we learn more ourselves, one of the things that generally began to bother me was the idea of what will happen when we’re not around. As we don’t really know how they’ll develop and what definitive impact the programs will have, we don’t know whether they will require care for their entire life or even what type of care that will be.

One of the obvious things that occurred to me is that perhaps this isn’t a matter of administering care but more about creating places in society that will not only allow them to have a certain quality of life but where they can integrate and contribute without needing to be “cared for”. In order for that to happen at first I believed that there needed to be a fundamental shift. But as I started to dig a bit more into this and make a plan for my sons’ future (part of that plan for example was for them to have a place of employment at my advertising agency), the idea that perhaps there’s always been a place began to emerge.

Think different.

People with ASD have differences rather than deficits. And being different is good. The creative industries have embraced this value for years. In the 90’s, Apple and Steve Jobs with the help of Chiat/Day and Lee Clow came up with the brilliant Think Different campaign. It challenged the status quo and celebrated those individuals who through sheer defiance, innovation and creativity changed our world for the better. This was an iconic campaign that is still celebrated today. The centerpiece of it was a 60 second spot, which began with “here’s to the crazy ones …” The film featured seventeen icons, eighteen if you include the later voiceover which was done by Steve Jobs. The originally aired spot used Richard Dreyfuss to narrate. Of those eighteen people, thirteen of them were either diagnosed or are suspected to be/have been on the autistic spectrum. That full list includes Albert Einstein, Bob Dylan, Martin Luther King Jr., Richard Branson, John Lennon, Buckminster Fuller, Thomas Edison, Muhammad Ali, Ted Turner, Maria Callas, Gandhi, Amelia Earhart, Alfred Hitchcock, Martha Graham, Jim Henson, Frank Lloyd Wright, Pablo Picasso, and Steve Jobs. Only MLK, Branson, Ali, Callas and Graham appear not to have been on the spectrum.

The entirety of the ad’s copy is here: Here's to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The trouble-makers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently. They're not fond of rules, and they have no respect for the status-quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify, or vilify them. But the only thing you can't do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward. And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

Ken Segall, creative director on the campaign commented as follows:

The ability to think creatively is one of the great catalysts of civilization. So the logic seemed natural: why not show what kind of company Apple is by celebrating the people Apple admires? Let's acknowledge the most remarkable people — past and present — who "change things" and "push the human race forward."

That’s incredible. The brief was never to create a film featuring a predominant cast of people on the autistic spectrum but rather to find historical figures who truly thought differently and changed the world. The spot ended with Apple’s now iconic “Think Different” signoff. For two decades, the advertising industry has celebrated that slogan as a calling cry for creativity and ideas that cut through. For work that truly set itself apart. Being different and producing work that was considered different won awards, clients and created great careers.

The Relationship Between Subthreshold Autistic Traits, Ambiguous Figure Perception and Divergent Thinking.

In August 2015, Catherine Best, Shruti Arora, Fiona Porter and Martin Doherty published an article in the Journal of Autism and Development Disorders called “The Relationship Between Subthreshold Autistic Traits, Ambiguous Figure Perception and Divergent Thinking”. In it, the authors explored the idea of creativity amongst people on the spectrum, in particular their ability and even affinity to create unique ideas and solutions.

In this article, they talked about a series of tests that they performed on a group of people, some of them on the spectrum and others being neurotypical. What they discovered is that of those tested, respondents with ASD delivered provided quantitatively unique solutions to problems. The answers they provided scored in the top 5% of least common answers amongst the entire group, meaning that this wasn’t subjective uniqueness but quantifiable. For example, researchers would show those being tested a paperclip and ask for them to suggest alternative uses for it. More common responses were a fish hook, a pin or a piece of jewelry, while people with ASD offered responses such as a ballast for a paper airplane, a metal binding clasp for flowers or poker chips.

What is thinking different?

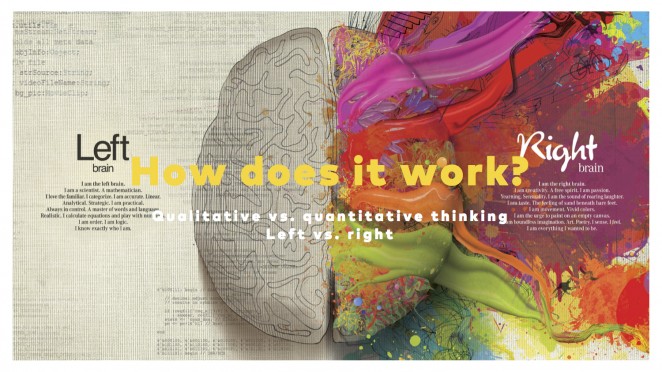

Our brain is divided into left and right hemispheres. The right side is considered the creative part and is responsible for things like immediate references, social engagement and episodic memory. The left side is the logical side of the brain and controls strategies, analytics and executive order decision-making. A neurotypical approach to creativity and problem solving starts on the right side and relies on immediate reference memories to help resolve issues. After exhausting those options, they then move to the left side of the brain and deconstruct the problem into its parts and look for more systematic solutions. The right hemisphere is generally impaired for individuals with ASD, while the left side functions conventionally, even advanced in some cases. Those people tend to immediately approach any creative conundrum by going straight to the left hemisphere and deconstructing the problem into its parts, arriving at ideas based on that deconstruction rather than relying on familiar association.

This is one reason why so much creative work in the advertising industry looks very similar. Neurotypical creatives rely on a common experience as a default solution to creative briefs and business challenges. Individuals on the autistic spectrum are simply wired differently. In the literal sense, they think differently because that’s the way they are set up.

Out of context.

Because people on the spectrum approach everything in a different way, they generally don’t share a common experience with neurotypicals. For example, when I watch a cartoon with my son Greg, we take away very different things. Greg has a high affinity for letters and numbers. So while we may both sit thought a 90-minute cartoon, he gets excited at the end when the film credits roll or during subtitles if they’re turned on. For him, that’s the best part. Same 90 minutes. Different takeaway experience. His context differs from mine as it does for other people with ASD. As a result of us having both a different context and a different approach towards reaching solutions, his ideas and responses will the quantifiably more unique. And being unique and different is really at the heart of creativity.

Societal legacy.

The creative field has always thrived with the ability to produce unique ideas and content. And it is for this reason that I believe that advertising and other similar creative industries are a front line for integrating these divergent thinkers into our society. In reality, inadvertently we already have but now it’s time to herald the obvious.

I look at all this in the context of a societal legacy. As many parents, I worry about my kids ability to take care of themselves and thrive. Understanding how to manage meltdowns in autism can provide a safe and nurturing environment for individuals on the spectrum, which in turn can foster their creativity and unique talents. Will they get a job? Will they connect with others? Will they be happy? I believe that our industry is one that can address this ongoing concern for those affected by ASD and help set an example for other sectors, societies and countries. In the ad field, we often struggle with the idea of whether what we do makes any real impact on society as a whole. I believe that it does and in the case of ASD, it can be so much more profound and lasting. We’ve always embraced thinking differently. All we need to do is continue staying that course.

Ben Woolf January 16th, 2018, at noon

Very interesting and thought-provoking article.Many thanks for sharing.